The Weiner Court of Muses

Der Weimarer Musenhof (1860); Schiller liest in Tiefurt

Theobald von Oer

If

enlightenment is an aspect of our true biological nature, we can make a

reasoned case for seeking out its continuation or presence in all other things.

If, however, by means of

technological advancement, we ultimately transcend the biological limitations

that have long-since defined the experience of being human, i.e., finite

existence, then the questions surrounding enlightenment may no longer hold our

imagination captive.

Discourse

Utilizing Kant’s Definition of

Enlightenment:

Discuss Rousseau, Kant and Marx as Enlightened

Figures

Kant’s (1724 – 1804) theory of enlightenment bridges the gap

between the rationalist and empiricist traditions of 18th century

Europe; a time characterized by dramatic revolutions in science, philosophy,

politics, and the social order. Despite spending his entire life in the town of

his birth, Königsberg (the then capital of Prussia; now Kaliningrad in Russia),

Kant is regarded as one of the most influential European philosophers since the

Ancient Greeks.

For Kant,

enlightenment was “man’s emergence from his self-incurred immaturity,” which,

if cultivated by means of his “natural endowments” (i.e., one’s own reason), could

serve to free him from the restrictions that prevent enlightenment. By this

reckoning, Kant would consider any scholar, who offered the public a “carefully

considered, well-intentioned thought on the mistaken aspects” of any doctrine,

an enlightened person, or at the very least, an individual freely acting out

“their own reason in all matters of conscience” in order to “liberate mankind

from immaturity”.

“It is a great and beautiful spectacle to see

a man somehow emerge from oblivion by his own efforts, dispelling with the light

of his reason the shadows in which nature had enveloped him, rising above

himself, soaring in his mind right up to the celestial regions, moving, like

the sun, with giant strides through the vast extent of the universe, and, what

is even greater and more difficult, returning himself in order to study man

there and learn of his nature, his obligations, and his end.”

Rousseau's

(1712 – 1778) explanation of human beings as initially existing in a “state of

nature is a highly romanticized one. He is thus known as the first philosopher

of Romanticism, and for his argument that human beings are innately good, but

have had their behavior altered by the corrupting influences of society. Given

Rousseau’s influence on Kant’s work, in particular in the area of ethics, we

can deduce that Kant considered Rousseau an enlightened figure.

The Happy Accidents of the Swing

Jean-Honoré Fragonard (1732 - 1806)

For Kant,

moral law is based on rationality, whereas with Rousseau, nature is a constant

theme that should not be ignored. Despite these differences, like Rousseau,

rather than ask the traditional question about whether our knowledge accurately

reflects reality, Kant asked how reality affected our cognition or

understanding. He attributed what we know as something that is determined by

the nature of our sensory and cognitive apparatus. More simply put, knowledge

starts with experience, which then requires ordering by the mind. Thus, it is possible

by means of our reason, to discover universal truths about our world.

Karl Marx

(1818 – 1883) thought that reality was historically constituted, containing

internal conflicts that drive change. Like Kant, Marx thought that external (economic)

forces affected our cognition and understanding.

Marx’s work

had a profound effect on world history, leading a third of the world’s

population to live under regimes claiming allegiance to his philosophy. Like

Kant, Marx believed that all concepts (including the processes belonging to

history) were open to rational investigation. In other words, the historical

situations upon which Marx based his philosophies were situations that

contained internal conflicts that could be alleviated.

Similar to

Rousseau’s explanation of how social or external influences affected the

natural state of mankind, Marx saw the inexorable logic driving the course of

history as material, rather than spiritual, evidence for changes, and

ultimately, the oppression of mankind, or more specifically, the worker. While

Rousseau perceived social influences as something that affected human action, Marx

further explained how those material forces, which affect human action, in

turn, served as the engine of social change.

Diego Rivera (1886 - 1957)

Diego Rivera (1886 - 1957)

For Marx, the

dialectical conflict between distinct socioeconomic classes that production and

distribution produce determines the course of history, driving social change, which

ultimately contributes to the nature of class conflict. Thus, the opium of the

people, accordingly, is that which sustains the status quo, the

“superstructural” social phenomena (such as political institutions, religions,

ideologies, philosophies, and the arts) that only serve the ruling class – the bourgeoisie.

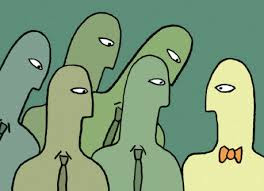

La Bourgeoisie (1894)

Émile Pouget

Much like

how 18th century philosophers experienced what their generation

considered to be inconceivable heights of intelligence, industrial progress,

and longevity; we again find ourselves on the brink of great social and

philosophical change, the ramifications of which will be profound for

enlightenment thinkers. The adjustments technological advancement pose present

a glimpse of the coming age that is both a dramatic culmination of centuries of

social, philosophical, and technological ingenuity as well as a genuinely

inspiring vision of what Kant meant by “enlightenment” (man’s emergence from

his self-incurred immaturity”). At the onset of the twenty-first century, two

hundred years after Kant’s death, humanity once again stands on the verge of reconsidering

what it means to be enlightened, not only in this discourse, but as a global

community living in an era in which technology will challenge the very nature

of what it means to be human will be both enriched and challenged.

*Disclaimer:

Rousseau, Kant and Marx are still in the bar discussing their theories of enlightenment.

.jpg)

No comments:

Post a Comment