Back Story

~

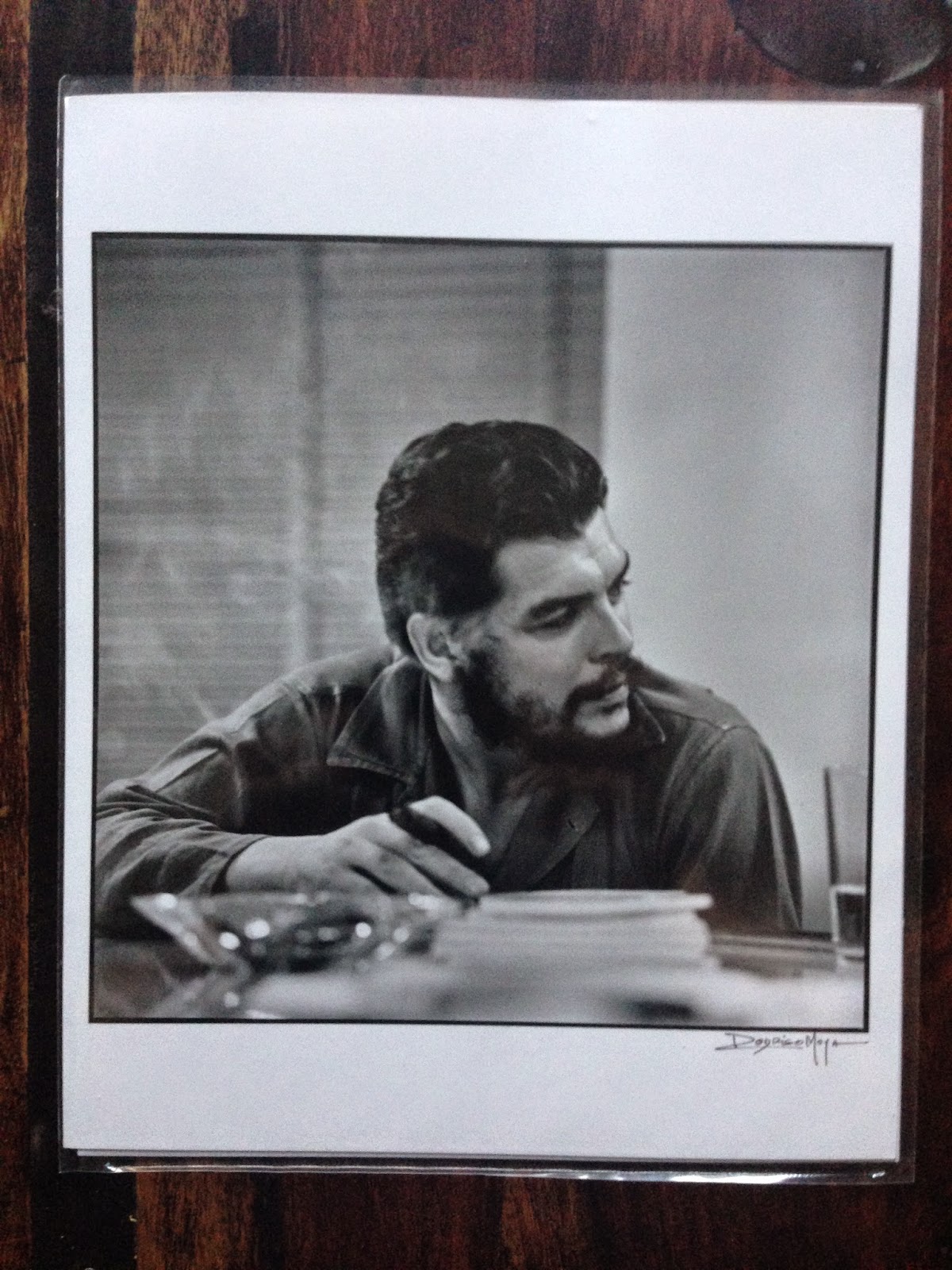

Ernesto "Che" Guevara (June 14, 1928 - October 9, 1967), known as Che, was an Argentine Marxist revolutionary, physician, author, guerrilla leader, diplomat, and military theorist. Together with Fidel Castro, he was a major figure in the Cuban Revolution (1953 - 1959), an armed revolt against Cuban President Fulgencio Batista. Replacing the government with a revolutionary socialist state, the movement later reformed as the Communist Party in October 1965. The Communist Party, now headed by Fidel Castro's brother Raúl, governs today.

Che Melancólico Series

Rodrigo Moya

Sometimes facial expressions are difficult to read, but other times they seem universal. In this photo, Che looks like he just took a deep breath and exhaled, letting go of some of the tension that marked these public conferences. At the same time, there is an untouched sense of wonder and trust that is palpable in his gesture.

There are times when we wonder from where motivation arises. I can't help wondering if Che was quietly searching for that spark within himself the very moment this picture was captured. This image is not a moment of depression, this is the aftermath of excessive feelings of euphoria; excessive irritability; difficulties concentrating; disturbed sleep patterns; and insufficient nutrition. This is that moment when analysis outstripped Che's capacity for synthesis.

Later he will probe and pull things back together, but for this one quiet moment, he was not focused on putting them back together. He was simply allowing himself "to be" ... synthesizing his impressions and thoughts in an unspoken gesture of quiet resignation that follows intensively significant states of hyper-vigilance and anxiety.

Che Melancólico Series

Rodrigo Moya

Here Che's moment of resignation rebounds into a need to gain mastery over a self-system in chaos. The recognition of disarray and disunity can be extremely terrifying for anyone, much less to a person in his situation at the time of these highly charged socio-political events. Thus, the need to rebound intensifies, bringing with it a new level of clarity and focus.

Whenever one disintegrates from one's surroundings, the following phase invites new ways of perceiving and increased self-awareness. In the state of true melancholy above, Che appears to have drawn himself into a state of self-analysis. In the subsequent phase of enhanced inspiration that follows melancholy, Che appears to have inspired himself with a vividness of associations. Rustling through the paperwork, the internal psychic milieu is strengthened, and higher-level association is supported.

Che Melancólico Series

Rodrigo Moya

The final image in the Melancholy stage is meaning, that yearning for reflection of a dynamic, and multifaceted inner world. Here, Che relights his cigar. The loneliness he suffered brought him from a stage of resignation to excitation, resting in a focused and strategic mindset. He appears pleased with himself; self-assured in his talent, knowing in his understanding of philosophy, politics, science, and human interactions.

Che is an academic, a deeply passionate individual silenced by the wonders of nature. Devoted to the highest ideals of the causes for which he has fought, Che finds within himself inspiration. Together with the facility of synthesis, and a vividness of association to push beyond his personal struggles and emerge, Che presents to the world an individual in possession of the mental status required for grave concern over the events which have transpired, as well as the required focus it takes to devise and execute a plan.

Che Gallardo Series

Rodrigo Moya

The "Gallant Che" series begins with an intellectual overexcitability. Faced with innumerable tasks and challenges, Che is sound enough of mind to recognize that his decisions and actions must be extraordinarily fluid. His ability to read and synthesize what must be done in order to co-participate in executing a well-ordered state is marked by the intense emotional expression on his face. This is a moment of extreme dissatisfaction with the unpleasantness of the tasks at hand. It is clear that he is hyper sensitive to the mood state of his environment. He must find that gentle encouragement from his cigar, which he relit prior to this image, in order to continue.

The marked anxiety is evident - his face is taut and his upper body is tense. Here, Che must again intellectualize most of his feelings. He seems a bit unsure and disoriented when evaluating the tasks at hand. In Che's facial expressions we are capable of reading social cues and of integrating what he might have been thinking or feeling. When overwhelmed, Che does not seem overly difficult to read. His latent interpenetrating perceptions and feelings are written all over his face.

Che Gallardo Series

Rodrigo Moya

The variety of different ways Che seems to have for integrating stimuli adds complex to this collection of photographs. His sensitivity and ability to rebound hint at an "unknown field" relating to both his inner and outer worlds. His disquietude coupled with excitation, the back and forth of doctor versus revolutionary forever at play.

In this photo the Revolutionary makes an appearance. There is a loosening of familiar processes, a new edge of creativity in one's own being, and the opportunity to forge true political change must have been heightened in his mind at this very moment. Che's counselor within attended to his grounding mechanisms by allowing for an earlier emotional discharge, but his warrior instincts put them to rest and got on with the job at hand.

The inner equilibrium of strong feelings of unreality, disconnection from society while in the jungle, and lack of personal cohesion must have caused Che's mind to spin, for great chaos revolves around itself in the utter destruction of everything familiar. After a point, there is no more suffering, only a neutral calm of total resignation (Melancholy Che).

Che was a thinker of exceptional quality, and all such thinkers know that they are thinkers without true knowledge. Reality lie somewhere along a stretch of interminable roads, and we are merely hitchhikers on that road; riding one piece of information until we arrive to the next.

Che Gallardo Series

Rodrigo Moya

Within this overall complex framework, Che's ability to probe his inner world and see multiple dimensions within himself and in the environment around him were noteworthy. It is evident in these photos that Che was consistently aware of others, of physical aspects of his environment, and of the social agenda from which he was physically separated during his time in the jungle. In many ways you could call his rebounding a positive from malady - a conflict with and rejection of the prevailing political party and attitudes without losing sight of a higher moral imperative that operated within Che's mind.

Che's outlook was a driving force in much of his behavior and thoughts. His challenge of the political structure and status quo in society was excessive, but it was also the impetus behind his growing complexity of mind.

Che Jovial Series

Rodrigo Moya

In the first photograph of Cheerful Che we see him returning to a state of contemplation, initiated notably by the complexity of the decisions facing him rather than the prior emotions that had invaded his earlier thoughts. Here, Che is visually focused on resolving a challenge as he looks off in the distance. It appears as if he is simultaneously listening to the conversation of another while gathering his own thoughts.

Che's profoundly introverted nature infused with rich imaginational, emotional, and intellectual characteristics was radically unlike those of Fidel Castro, the chief orchestrator of the overthrow of the then United States-backed military junta of Cuban president Fulgencio Batista. Castro's ultimate success in Cuba was using intelligence to maintain efficient systems. Castro became the 'father' of Cuba, providing a state for his 'family' (all Cubans, and honorary Cubans) rather than a state for just the citizens of Cuba.

The legacy of the Cuban Revolution was in taking a long history of deep mistrust of intellectual pursuits and shifting that distrust into a firm adherence to a philosophy of pragmatism. Both Che and Fidel were extremely successful in achieving their revolutionary goals, but prone to unbalanced displays of emotion and unreasonable acts. Like Che, Fidel is complex. As Revolutionaries, both cared deeply for the rights of the unfortunate. The Revolution was a way to support their idealistic, passionate, tenacious, and complex style of operating in the world.

Che Jovial Series

Rodrigo Moya

The vast mood improvement in this photo marks Che's inherent sense of well-being and a resurgence of hope and purpose. With profound challenges comes profound opportunities for therapeutic encounters of deep meaning and sufficient complexity that can help facilitate the transformation of cognitive functioning, emotional fatigue, and stymied processes of living in the world.

For Che, exceptional sensitivity and almost immeasurable intensity were fundamental features in the challenges he experienced. His rich inner world and his capacity for deep intellectual, emotional, and imaginational penetration into the world around him resulted in a surplus of feelings and impressions that were exacerbated by a revolutionary environment.

Understanding the thoughts that lie behind Che's facial expressions demands a great deal in terms of conceptual sophistication and sensitivity in analysis. Not being trained in psychology (other than a few courses in college), I can only rely on what my own inner thoughts tell me when I look at these images. Even for a trained psychoanalyst, anyone wishing to examine the feelings, motivations, or thoughts of another must first examine these sensitivities in him or herself. Without a meaningful exchange with the individual - which in this case is impossible - any theory we interpret is a co-creation with our own inner world.

More than anything, in this photo Che appears relieved - even if only for a moment. Maybe he sees the transformational potential in what had previously been seen as merely dysfunctional issues, which speaks to the individual growth process that follows profound surges in emotional, intellectual, and physical challenges.

Here, Che seems more authentic. His personality comes forth and we find reason to like him, considering the person behind the Revolutionary Figure.

Che Jovial Series

Rodrigo Moya

"You talkin' to me?"

Several moral and ethical themes recur across these photographs - Che's awareness and concerns with justice, his concern for the well-being of the downtrodden; questions of right, wrong, and the relativism of these concepts; questioning death and his role in saving or ending a life; and interest in philosophy and social issues.

As a child, Che must have been naturally very curious. We know that he read voraciously, and paid close attention to the world around him. It is almost as if he had been hyper-vigilant. Not only did he pay close attention to what other people were doing, but he was conscious of what other people's actions meant. Che must have begun processing moral and ethical issues at a very young age, which motivated his education and infamous road trip (The Motorcycle Diaries).

Initially, upon meeting individuals like Che, others are usually touched by their sense of caring and concern, yet at the same time frequently feel concern for how and what extent to delve into these areas. Many young children act on this early awareness and sense of responsibility by volunteering at school or in their communities to make a positive contribution toward issues that concerned or inspired them.

Che, on the other hand, adopted the humane issues of a country other than his own. Perhaps this 'outsider' attitude is what is at play in this photograph. It is that "I have a right to be here" look while simultaneously questioning that right in the person to whom he is responding.

Irrespective of how much one comes to the aid for another, the sense of having a 'right to be there' comes up for all parties, those who offer aid as well as those who are being aided.

Che Locuaz Series

Rodrigo Moya

While Moya titled this series Loquacious Che, I see in these last three images a stage that is characterized by integrity versus satisfaction. Rather than being satisfied with the successes of the Revolution, Che looks as if this marked the beginning of his projecting his deeply held personal views onto the world stage.

The high-powered brain that drives a person like Che does not switch into low gear simply because a milestone has been reached. For Che, who emerged as a "revolutionary statesman of world stature" (Kellner, 1989), the conflict continued. The struggle of the masses mistreated and scorned by imperialism needed help and deserved vindication.

The laws of capitalism, blind and invisible to the majority, act upon the individual without his thinking about it. He sees only the vastness of a seemingly infinite horizon before him. That is how it is painted by capitalist propagandists, who purport to draw a lesson from the example of Rockefeller - whether or not it is true - about the possibilities of success. The amount of poverty and suffering required for the emergence of a Rockefeller, and the amount of depravity that the accumulation of a fortune of such magnitude entails, are left out of the picture, and it is not always possible to make the people in general see this."

("Socialism and Man in Cuba" A letter to Carlos Quijano, editor of Marcha, a weekly newspaper published in Montevideo, Uruguay; published as "From Algiers, for Marcha: The Cuban Revolution Today" by Che Guevara on March 12, 1965).

Che Locuaz Series

Rodrigo Moya

While Fidel Castro settled in to run things at home, Che embarked on a series of public appearances on the international stage, delivering speeches on solidarity. He resigned from all his positions in the Cuban government and communist party, renounced his honorary Cuban citizenship, and went to fight for revolutionary causes abroad.

It is not surprising that Che's life came to an end while fighting the good fight. Here in this photograph there is something in Che's eyes that tells the onlooker that he has not outgrown the initial revolutionary ideals he adopted. On the contrary, he is firm and steadfast in his beliefs; more so now, than perhaps in the beginning. There is an intensity in his gaze, a complexity that would elicit an equally intense reaction in anyone who looked directly into his eyes.

It is not easy to orchestrate a Revolution, educate and train a fighting force, or establish radio broadcasts and schools from outposts in the jungle; vision, coordination, and reaction time needed in survival circumstances become heightened.

How does a high-functioning mind respond to these heightened experiences? Not by retiring, that's for sure. It was not about substituting one ideal for another. For Che, humanism was the ideal. He must have felt that he had no other way of expressing this ideal than to continue fighting.

Che Locuaz Series

Rodrigo Moya

Why did he fight for the rights of foreign citizens?

Che was anything but weak. He was handsome, highly intelligent, and beyond capable. Had he chosen to do so, he could have revolutionized Cuba into his vision of a model society. Instead, he left again to fight the good fight. Again, we ask why.

The answer to this question speaks to the intensity of individuals like Che. People who become the byproducts of a lifelong investment in mental challenges. Usually, these individuals have above-average educations, enjoy complex and stimulating lifestyles, and are married to smart ideals. This intensity is not something that is outgrown, if anything, it increases with age.

Individuals like Che continue to seek, find, and create new challenges for themselves. They work tirelessly, using their gifts and talents in meaningful ways toward their goals of making the world a better place. Many are lifelong learners and seekers of truth. Che's life was an extension of his inner experiences, his death a result of earlier phases and the repercussions associated with living a highly intense socio-political life. Associating oneself with dissenters invites dissent, which typically transcends the boundaries of dissenter and Revolutionary Hero. Che, in many ways, became a dissenter, or maybe he always was. His identification with the downtrodden spoke to an internal loneliness he must have felt in childhood. Without kindred spirits with whom to commune on the profound subjects that speak to a highly intense person, that same highly intense person begins to commune alone. Even in good company, solitary communion can leave an individual vulnerable to unhealthy mental constructs.

While Che had highly developed coping skills to combat these challenges, he pushed the limits to the point when his revolutionary actions became nothing more than a numbers game. Eventually the game ended.

The game doesn't always have to end in tragedy. Sometimes the game can end peacefully and quietly, with few if any realizing that a game had ever been played. These individuals live in exile from their former selves and from their former lives. The intensity is still there, only it is redirected. Where it is redirected often times relates more to what the individual enjoyed before the intensities of their complex mindset evolved.

This return to self is familiar for many people; not necessarily on the same level of intensity as was the life of Che Guevara, but a level involving an extension of experiences rather than a final chapter or conclusion. It is natural to "miss" a prior mindset once circumstances no longer require its presence, but a highly intense individual in possession of a healthy mindset will inherently find a way to redirect that longing into a longing for the new activities he or she adopts.

No comments:

Post a Comment