"Public art punctuates our surroundings"

~Timothy P. Whalen, Director

Getty Conservation Institute

East First Street off First Avenue in Manhattan

My fascination with public artworks began as a child. Drawing flowers, buildings, cartoon characters, tic-tac-toe games, circles, squares, and any object that captured my attention or flowed from my tiny fingers. My chalk and I were great friends, and best of all, my family could wash the sidewalk off once I was finished.

No one took photos of my chalk-works. Instead, my family came out to simply admire my creations, while my friends came out to actively participate in the hopscotch games I had sketched. My hopscotch chalk-works were comprised of more than simple boxed squares and numbers, they had borders, flowers, and characters hanging off the sides as if falling through the ground.

The temporality of the experience left a marked impression on my mind, one that I interpreted as art is something to create, again and again, for the sole purpose of entertaining oneself and others.

Unlike the artworks that are housed in the controlled environments of museums, public artworks interact with the world at large. Ephemeral in nature, their focus is to delight, surprise, communicate or engage with those who come upon them.

The natural tendency to artistically express ourselves dates back to prehistory when our predecessors drew on cave walls, on the sides of caverns or mountains, across vast valleys, on pottery, on fabrics, and on themselves. The tendency to create outside oneself is inherent. Whether creation occurs within the confines of an art studio or on the sidewalk of Italy's Piazza, the autodidactic tendency to express oneself through works of art is abundant and shared across cultures, landscapes, and eras.

Cueva de las Manos (Cave of Hands)

13,000 - 9000 BCE

Argentina

Despite the freeing and inherent nature associated with creating public artworks, there are many conservation issues associated with outdoor painted surfaces, sculptures and murals. The properties and behaviors of paints used, human activity. The power of climate and decay affect art, contributing to the temporality of it when it is not preserved by modern art conservators. Philosophically speaking, public art requires us to pause and reflect whether or not these works of art should be preserved, or if they should just be washed away like the chalk drawings of my childhood.

Ethics of Conservation

Ethics, dating back to the time of the ancient Greeks, is primarily concerned with 'How one should live one's life.' While this personal reflection is related to moral behavior, implicit is the question of how human beings should relate to one another.

If the modern world has taught us anything it is how fundamentally we affect one another's lives. Our relation to our contemporaries, our descendants, and our environment bring up questions of sustainability, which reflects our concern for preserving art for future generations. Of course, there is the counter that what is touched by humans is devalued (Colwell, 1989), suggesting that only what is wholly natural is truly irreplaceable and therefore worth every effort to conserve. What humans have shaped they can shape again, thus destruction matters less (according to some).

Nature renews itself despite human assaults, artistic assaults, included. While the ethics of conservation with respect to public art are debatable and in their infancy in terms of defined practices, artists who feel compelled to create public art and well as those who enjoy viewing public art share aesthetic concerns. If we did not, we would not take offense to neighbors who fail to mow their lawn, or to individuals who litter and/or deface public buildings.

Enjoying Public Art

"Wilderness is the raw material out of which man has hammered the artifact called civilization" (Leopold, 1949). With this being said, the high value industrialized societies place on art is evident in the fact that many buildings are preserved due to the artwork adorning the often times dilapidated walls. It is the artwork or provenance that is of great importance, especially to the owner. There are a number of reasons why provenance is important, in particular in a piece of art's relationship to other artworks. If the artist becomes well-known, if the owner of the property is well-known, or if the location is of historical significance, the provenance becomes more highly valued.

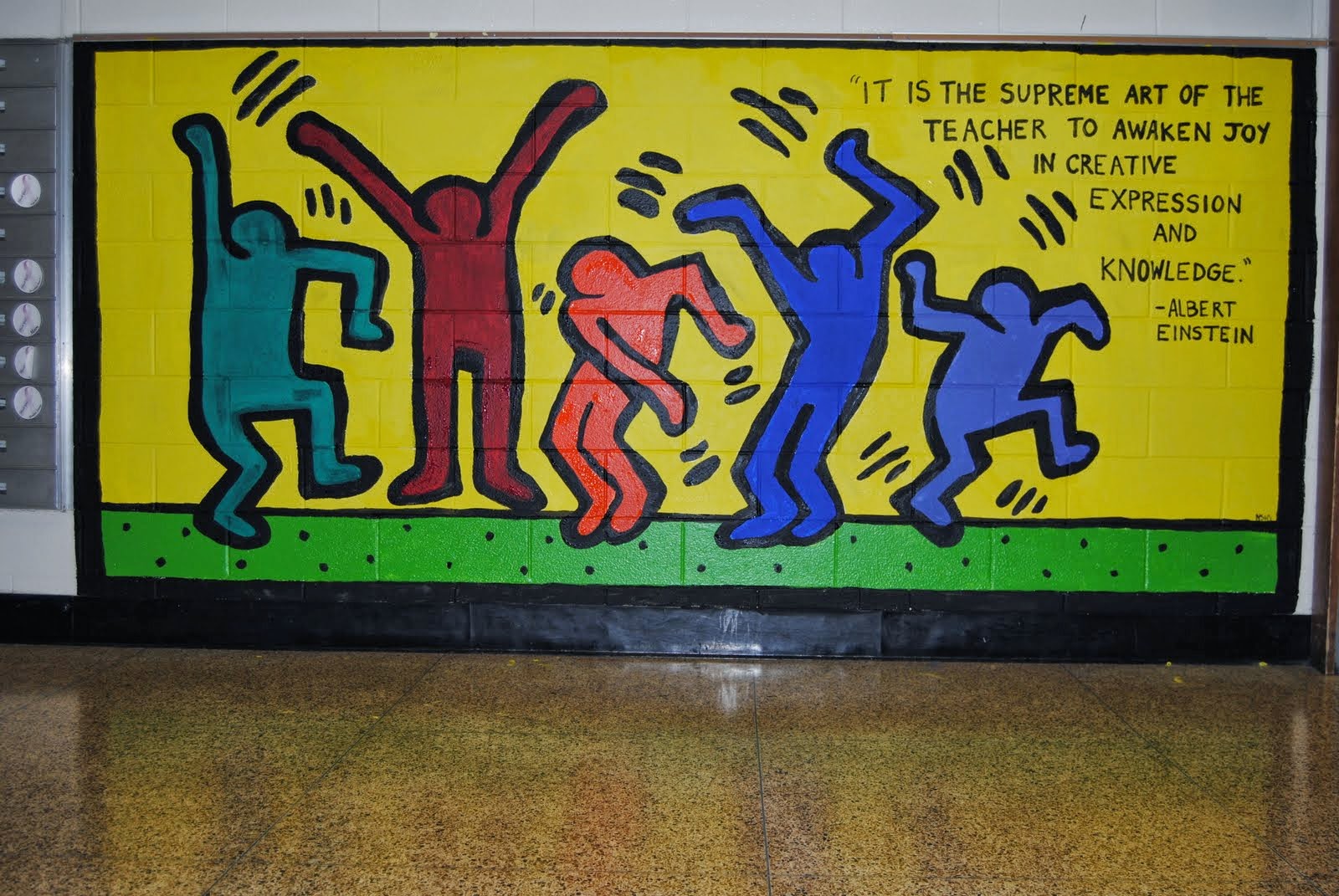

The quality of the provenance of a public work increases its selling price as well as public interest in conservation and preservation. Tiled walls in the subway graffitied by Keith Haring, for example, might be considered by some as historical landmarks, a categorical distinction above public art. Courts establish precedents that establish significant legal principles involving the distinguishing of a historical landmark, affirming the importance of public interest in historic preservation.

Moai Statues

1250 - 1500 CE

Polynesia's Easter Island

Here, we return, once again, to the ethics of conservation: preserving public art for future generations. The constitutional framework created by public opinion fosters a remarkable blossoming of historical preservation as a major tool of urban land use. As a species, as a culture, we "like" our public art. We enjoy making it. We enjoy viewing it. We strive to protect it for others to view and enjoy.

When we see a piece of public art that we love, in addition to photographing it, in addition to concerning ourselves with conservation issues, our primary concern should be personal enjoyment. To sit there and soak it up, to truly "take it in" and experience the art, this is what most agree is important.

Art is all about the experience, the artwork is simply an artifact of that experience.

No comments:

Post a Comment